March 9, 2023 – From TikTok to kombucha tea, gut health is having a moment – after we’ve already been hearing about it for years. Rightly so.

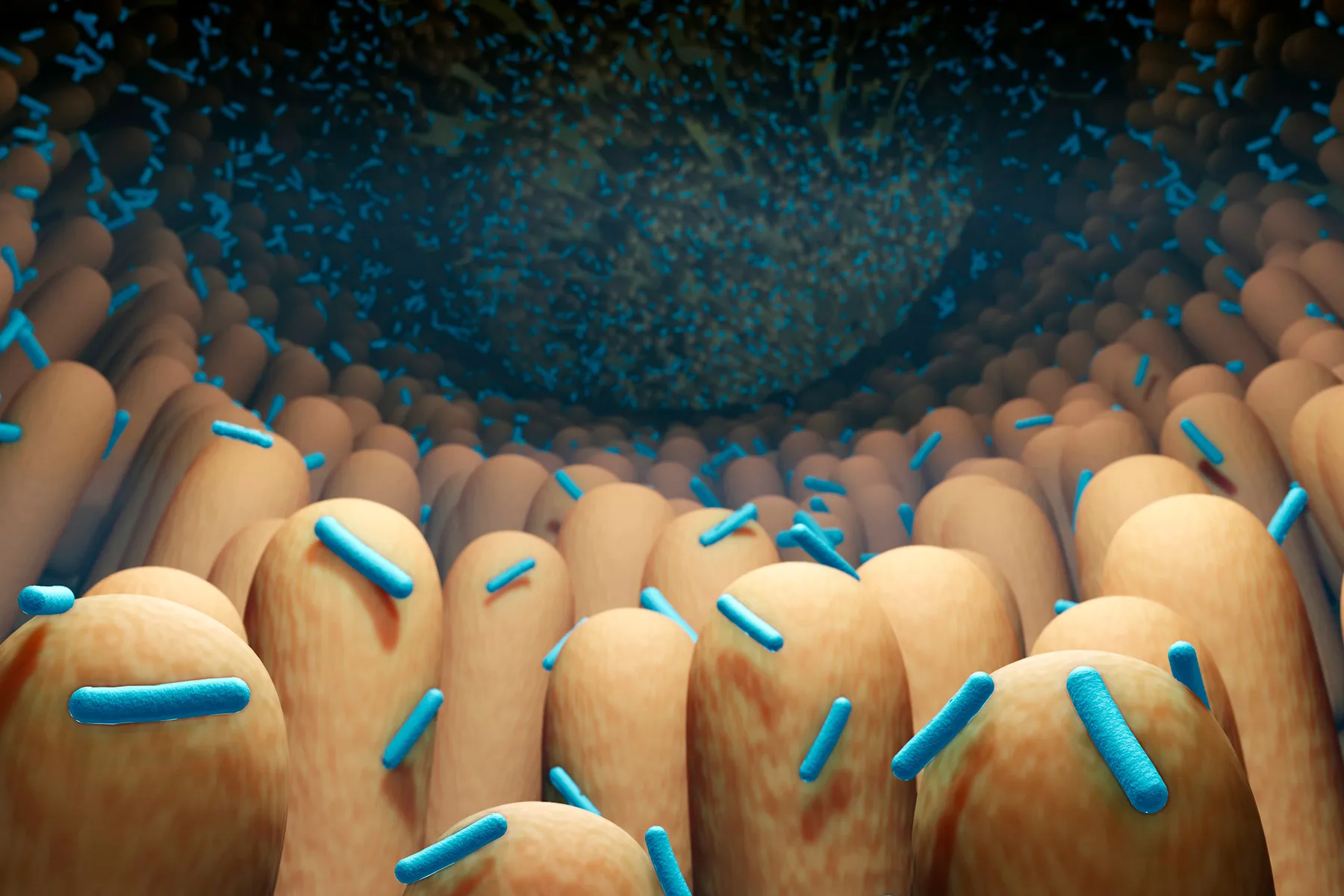

Your gut – and its diverse mix of bacteria known as the microbiome – is no longer just about digestion. Gut “health” is also linked to the health of your heart, brain, immune system, and more.

The problem: Much about what’s going in in there and what bacteria populate it at what levels – and how to interpret it all – remains a mystery. Studying the gut is tricky. Animal research may not be useful, because animals have different digestive enzymes and gut bacteria than humans do. And typical lab tests, like growing cells in a petri dish, don’t capture how complex the gut is, a part of the body where many types of cells grow and interact in a moist, flowing, oxygen-free environment.

An emerging technology, called “gut on a chip,” promises to change all that, opening the door to experiments never before possible and promising to advance medical research, according to a new paper in APL Bioengineering.

Your Gut on a Chip

It’s among the latest advances in “organ on a chip” technology, the concept of putting human cells in a device designed to mimic the activity of human organs. Scientists have developed models to simulate such organs as the lung, kidney, and vagina.

To build a gut on a chip, scientists culture cells from gut tissue and bacteria.

“These cells don’t grow easily,” says study author Amin Valiei, PhD, a post-doctoral scholar at the University of California, Berkeley. “They need a specific environment.”

To create that environment, researchers put the cells inside tiny channels designed to allow the flow of fluids and mimic forces found in the gut. That means the cells can interact with each other as they would inside the human body.

“These models are getting more and more advanced,” says Valiei. “Compared to a couple years ago, we now have models that can accommodate a few types of cells.”

Why This Matters: Drugs, Disease, and Dysbiosis

Researchers can do experiments on the models that would be difficult or impossible in humans.

“These devices could be especially useful in the hypothesis stage to test new drugs and therapeutics,” says Valiei.

Valiei and his colleagues at UC Berkeley’s Molecular Cell Biomechanics Lab are studying how different bacterial species interact in these gut-chip models. In particular, they’re exploring how certain harmful bacteria can take hold in the gut – a phenomenon known as dysbiosis that’s linked to a range of conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), diabetes, obesity, cancer, and heart problems.

Researchers are also using gut-on-a-chip models to study IBD, colorectal cancer, and even the effects of viruses like COVID-19 on gut function.

To understand how diseases develop, we need to break things down into fundamental steps, and gut-on-a-chip models could help researchers do that, says Christopher Chang, MD, PhD, a gastroenterologist at the Raymond G. Murphy VA Medical Center in Albuquerque, NM, and the University of New Mexico. (Chang was not involved in the study.)

“We can identify literally thousands of species in the gut, and we sort of know, in broad strokes, what microbes are considered beneficial, and what microbes are considered not beneficial,” he says.

But how do individual bugs fit into a community? And what combinations lead to a healthy gut versus an unhealthy one? Answers to these questions remain unclear.

“We have ways to manipulate the microbiome, through different antibiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplants,” Chang says. “But we need to know: What should we be manipulating?”

Room for Improvement

One part of the gut not yet reflected in gut chip models is the enteric nervous system, aka our “second brain” – neurons embedded in the GI tract, says Chang. This is how the gut and brain communicate, and its dysfunction is linked to bowel disorders such as IBS.

People with IBS can have pain, diarrhea, or constipation even though their gut tissue looks normal on biopsies. Gut-on-a-chip models might be less helpful in revealing insights about these disorders, though they could still help answer fundamental questions.

The gut-brain connection is still being clarified, so as the science evolves, researchers may be able to add new insights to future gut-on-a-chip models.

Gut-on-a-chip models could be useful beyond disease, too, says Valiei. Any medication you swallow goes through your GI tract. If researchers can use gut-on-a-chip models to uncover precisely how we digest and absorb medications, they might be able to refine how we use these drugs.

For now, the push is on to get this tech into widespread use. Because of the need to do more research, refine the tech, and gather enough data to satisfy regulators, it may still be several years until this kind “precision” medicine will be precise enough to truly personalize its use for patients. But according to Valiei, this is indeed an accurate glimpse of what’s to come.