Feb. 22, 2024 — Injectable weight loss drugs like Wegovy, Saxenda, and Zepbound have been getting all the glory lately, but they’re not for everyone. If the inconvenience or cost of weight-loss drugs isn’t for you, another approach may be boosting your gut microbiome.

So how does one do that, and how does it work?

“There are a lot of different factors naturally in weight gain and weight loss, so the gut microbiome is certainly not the only thing,” said Chris Damman, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Washington. He studies how food and the microbiome affect your health. “With that caveat, it probably is playing an important role.”

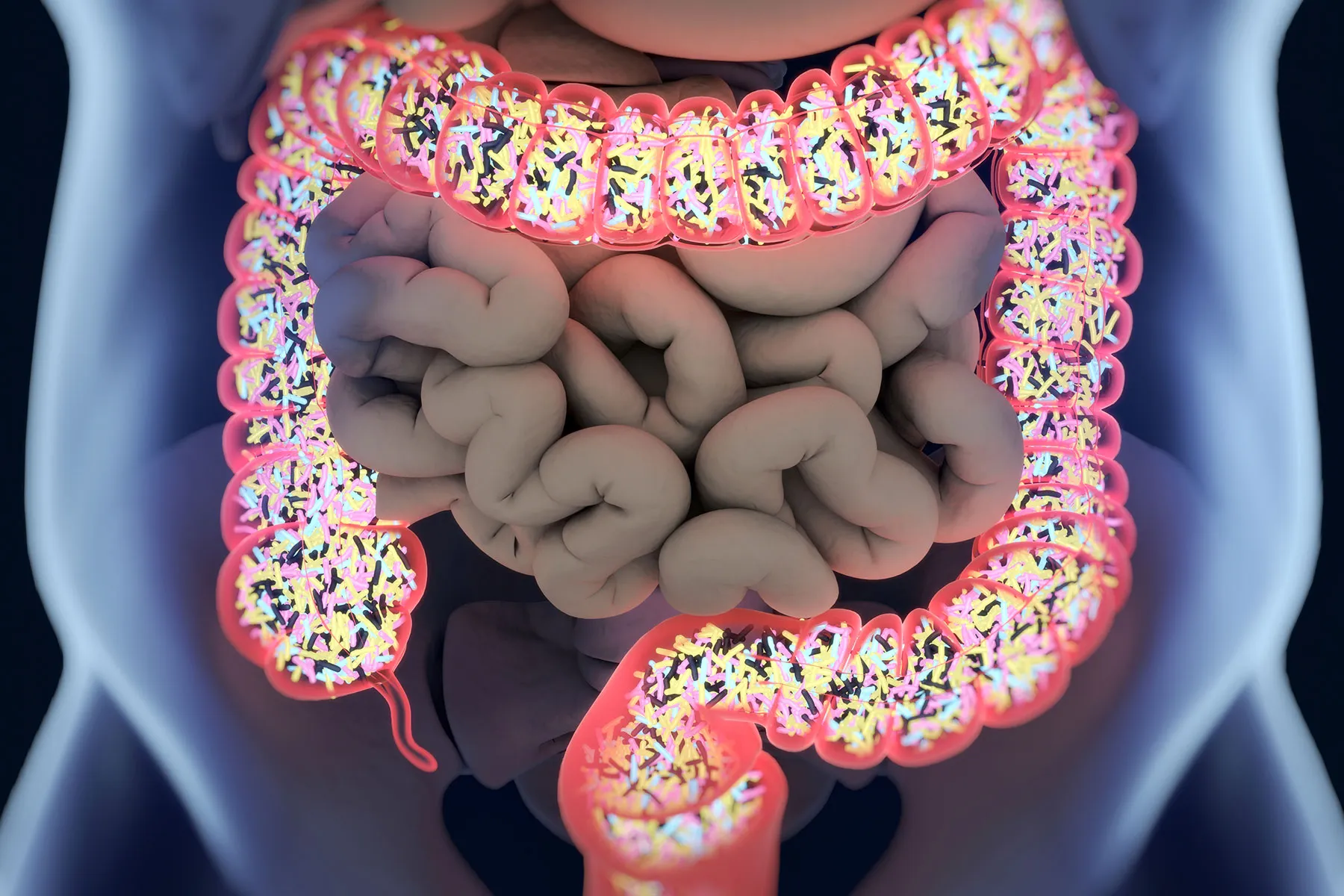

Trillions of Microbes

The idea that your gut is home to an enormous range of tiny organisms — microbes — has existed for more than 100 years, but only in the 21st century have scientists had the ability to delve into specifics.

We now know you want a robust assortment of microbes in your gut, especially in the lower gut, your colon. They feast on fiber from the food you eat and turn it into substances your body needs. Those substances send signals all over your body.

If you don’t have enough microbes or have too many of the wrong kinds, it influences those signals, which can lead to health problems. Over the last 20 years, research has linked problems in the gut microbiome to a wide variety of conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, metabolic ones like diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, asthma, and even autism.

Thanks to these efforts, we know a lot about the interactions between your gut and the rest of your body, but we don’t know exactly how many things happen — whether some teeny critters within your microbiome cause the issues or vice versa.

“That’s the problem with so much of the microbiome stuff,” said Elizabeth Hohmann, MD, a physician investigator at the Massachusetts General Research Institute. “Olympic athletes have a better gut microbiome than most people. Well, sure they do — because they’re paying attention to their diet, they’re getting enough rest. Correlation does not causation make.”

The American Diet Messes With Your Gut

If you’re a typical American, you eat a lot of ultra-processed foods — manufactured with a long ingredients list that includes additives or preservatives. According to one study, those foods make up 73% of our food supply. That can have a serious impact on gut health.

“When you process a food and mill it, it turns a whole food into tiny particles,” Damman said. “That makes the food highly digestible. But if you eat a stalk of broccoli, a large amount of that broccoli in the form of fiber and other things will make its way to your lower gut, where it will feed microbes.”

With heavily processed foods, on the other hand, most of it gets digested before it can reach your lower gut, which leaves your microbes without the energy they need to survive.

Rosa Krajmalnik-Brown, PhD, is director of the Biodesign Center for Health Through Microbiomes at Arizona State University. Her lab has done research into how microbes use the undigested food that reaches your gut. She describes the problem with processed foods this way:

“Think about a Coke. When you drink it, all the sugar goes to your bloodstream, and the microbes in your gut don’t even know you’ve had it. Instead of drinking a Coke, if you eat an apple or something with fiber, some will go to you and some to the microbes. You’re feeding them, giving them energy.”

Weight and Your Gut Microbiome

The link between gut health and body weight has received a lot of attention. Research has shown, for example, that people with obesity have less diversity in their gut microbiome, and certain specific bacteria have been linked to obesity. In animal studies, transplanting gut microbes from obese mice to “germ-free” mice led those GF mice to gain weight. This suggests excess weight is, in fact, caused by certain microbes, but to date there’s scant evidence that the same is true with humans.

Krajmalnik-Brown’s group did an experiment in which they had people follow two different diets for 23 days each, with a break in between. Both provided similar amounts of calories and macronutrients each day, but via different foods. The study’s typical Western menu featured processed foods — think grape juice, sandwiches made with deli turkey and white bread, and spaghetti with jarred sauce and ground beef. The other menu, what researchers called a “microbiome enhancer diet,” included foods like whole fruit, veggie sandwiches on multigrain buns, and steak with a side of whole wheat spaghetti.

While the study wasn’t designed for weight loss, an interesting thing happened when researchers analyzed participants’ bowel movements.

“We found that when you feed subjects a diet designed to provide more energy to the microbes and not to the [body], our subjects lost a little weight,” Krajmalnik-Brown said. “It looks like by feeding your microbes, it seems to make people healthier and potentially even lose a little.”

Another possible mechanism involves the same hormone that powers those injectable weight loss drugs. The lower part of your gut makes hormones that tell the entire gut to slow down and also help orchestrate metabolism and appetite. Among them is GLP-1. The drugs use a synthetic version, semaglutide or tirzepatide, to trigger the same effect.

According to Damman, you can stimulate your gut to make those helpful hormones with the food you eat — by giving your microbes the right fuel.

Eat to Feed Your Microbes

The foods you eat can affect your gut microbiome, and so your weight. But don’t go looking for that one perfect ingredient, experts warn.

“Oftentimes we get this micro-focus, is this a good food or a bad food?” warned Katie Chapmon, a registered dietitian whose practice focuses on gut health. “You just want to make sure your microbiome is robust and healthy, so it communicates that your body is running, you’ve got it.”

Instead, try to give your body more of the kinds of food research has shown can feed your microbiome, many of which are plant-based. “Those are the things that are largely taken out during processing,” Damman said. He calls them the “Four Fs”:

- Fiber: When you eat fiber-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and beans, your body can’t digest the fiber while it’s in the upper parts of your GI tract. It passes through to your lower gut, where healthy bacteria ferment it. That produces short-chain fatty acids, which send signals throughout your body, including ones related to appetite and feeling full.

- Phenols: Phenolic compounds are antioxidants that give plant-based foods their color — when you talk about eating the rainbow, you’re talking about phenols. The microbes in your gut feed on them, too. “My goal for a meal is five distinct colors on the plate,” Chapmon said. “That rounds out the bases for the different polyphenols.”

- Fermented foods: You can get a different kind of health benefit by eating food that’s already fermented — like sauerkraut, kimchi, kefir, yogurt, miso, tempeh, and kombucha. Fermentation can make the phenols in foods more accessible to your body. Plus, each mouthful introduces good bacteria into your body, some of which make it down to your gut. The bacteria that are already there feed on these new strains, which helps to increase the diversity of your microbiome.

- Healthy fats: Here, it’s not so much about feeding the good bacteria in your microbiome. Damman says that omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, canola oil, some nuts, and other foods, decrease inflammation in the lining of your gut. Plus, healthy fat sources like extra-virgin olive oil and avocados are full of phenols.

Eating for gut health isn’t a magic bullet in terms of weight loss. But the benefits of a healthy gut go far beyond shedding a few pounds.

“I think we need to strive for health, not weight loss.” Krajmalnik-Brown said. “Keep your gut healthy and your microbes healthy, and that should eventually lead to a healthy weight. You’ll make your microbes happy, and your microbes do a lot for your health.”